A Basic Usage of MinIO for Image Hosting

Created April 19, 2024While working on a project for my senior capstone course my group needed some kind of object storage for our website to function. Our website was a social image-sharing platform similar to Flickr and users could upload images to share with other people. However, we didn’t have anywhere to store them, and we didn’t want to keep binary data in our database.

Thankfully, the professor hooked us up with an on-prem MinIO cluster that we ended up using to store all the images uploaded to the website. I’ll go over how our set up looked like, and how MinIO made things incredibly easy to get everything working.

For the front and backend we used SvelteKit and we created a few endpoints for uploading images, serving them, and deleting them. These were the only places that would interact with MinIO so it was pretty simple to set up.

MinIO client setup

We needed to be able to use the MinIO client in several places so we made one utility file with it. All the private info is stored in .env of course, and SvelteKit can access those variables from $env/static/private. From my understanding, we don’t worry about SSL since all the traffic between web server and MinIO is on an internal network on campus. Only the SvelteKit server will be handling user requests.

// File: /src/lib/server/minio.js

import * as Minio from "minio";

import { MINIO_ENDPOINT, MINIO_ACCESS_KEY, MINIO_SECRET_KEY } from '$env/static/private';

export const minioClient = new Minio.Client({

endPoint: MINIO_ENDPOINT,

port: 80,

useSSL: false,

accessKey: MINIO_ACCESS_KEY,

secretKey: MINIO_SECRET_KEY,

})Uploading images

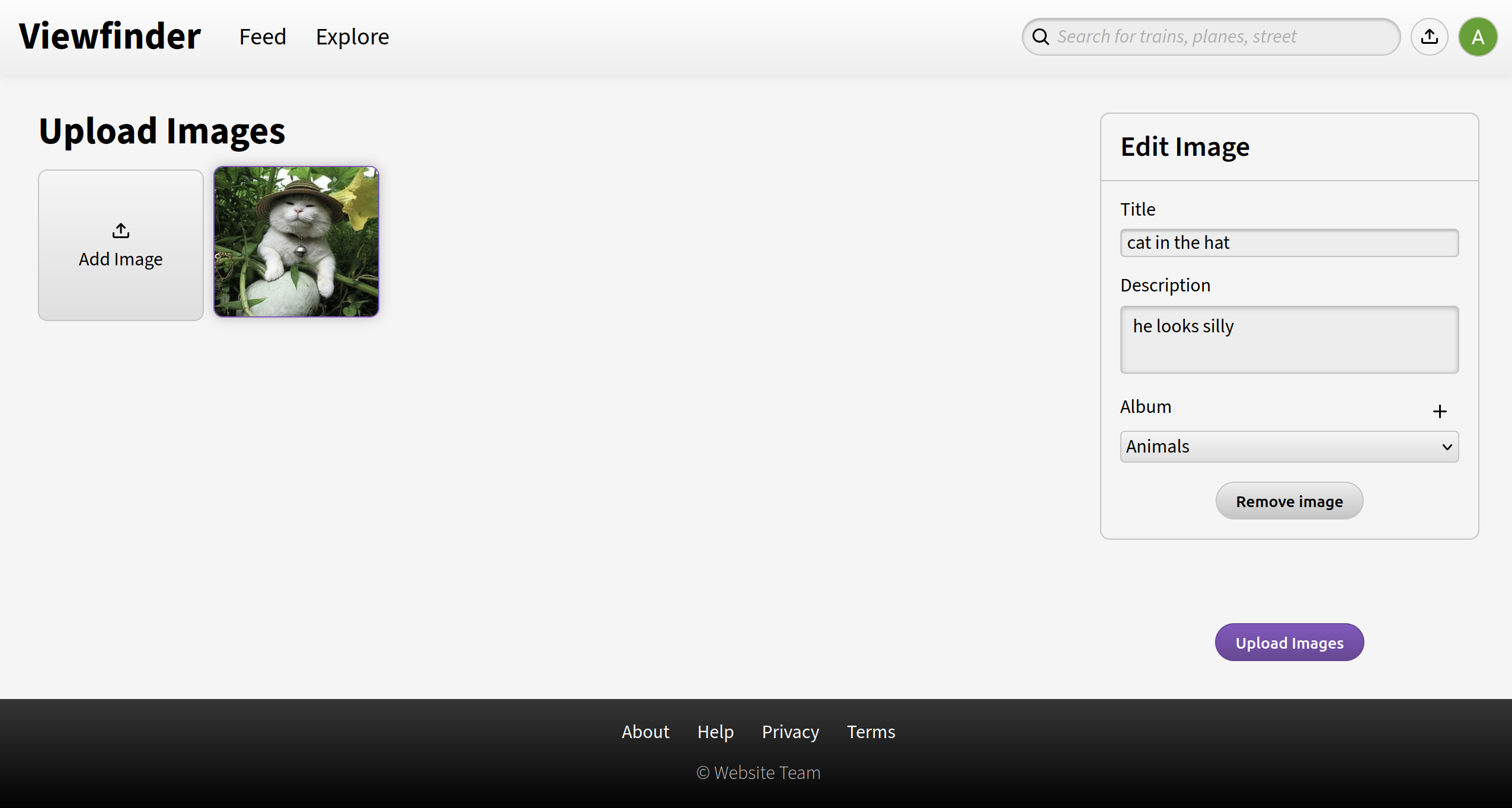

To start, the user goes to our upload page and adds any images they would like to upload. Next, they can fill in information about their photos like title and description, etc.

When the user clicks upload it gets sent to our upload endpoint as FormData:

// File: /src/routes/api/upload/+server.js

import * as db from '$lib/server/mariadb';

import { minioClient } from '$lib/server/minio';

import { lucia } from '$lib/server/auth';

import { randomUUID } from 'crypto';

import { S3_BUCKET_NAME } from '$env/static/private';

/** @type {import('./$types').RequestHandler} */

export async function POST({ request, cookies }) {

// [... User auth stuff omitted]

const UUID = randomUUID();

const photo = Buffer.from(await formData.get('photo').arrayBuffer());

const photoMetadata = {

title: formData.get('title'),

description: formData.get('description'),

albumId: formData.get('albumId'),

tags: formData.get('tags'),

};

return minioClient.putObject(S3_BUCKET_NAME, UUID, photo)

.then(res => {

console.log(res);

return db.uploadPhoto(user.id, UUID, photoMetadata)

.then(res => {

console.log(res);

return new Response(JSON.stringify({ message: "Image uploaded successfully."}), { status: 200 });

})

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

return new Response(JSON.stringify({ error: "Failed to upload image."}), { status: 500 });

});

};Once we receive the FormData object we can get the file blob from it, and the all the metadata. This seemed like the easiest way to combine the metadata and image file itself and it ended up working for our needs. I’m sure there’s a cleaner way to do it.

Unfortunately, you can see we have to do some weird manipulation for the photo to get turned into the correct format expected by the MinIO client. I’m not sure why, but after some tinkering this worked and doesn’t seem to cause any problems.

The image objects are given a random UUID name. We omitted the file extension here for some reason, but in the future I would include it since the images have no extension when you try to download them.

The JavaScript MinIO client uses promises and so does our database client, so we just string a couple functions together and it seems to work. First the image is uploaded to the MinIO cluster, and then an entry is created in our database. In theory, this should prevent empty entries from being created if something goes wrong during the upload.

Serving images

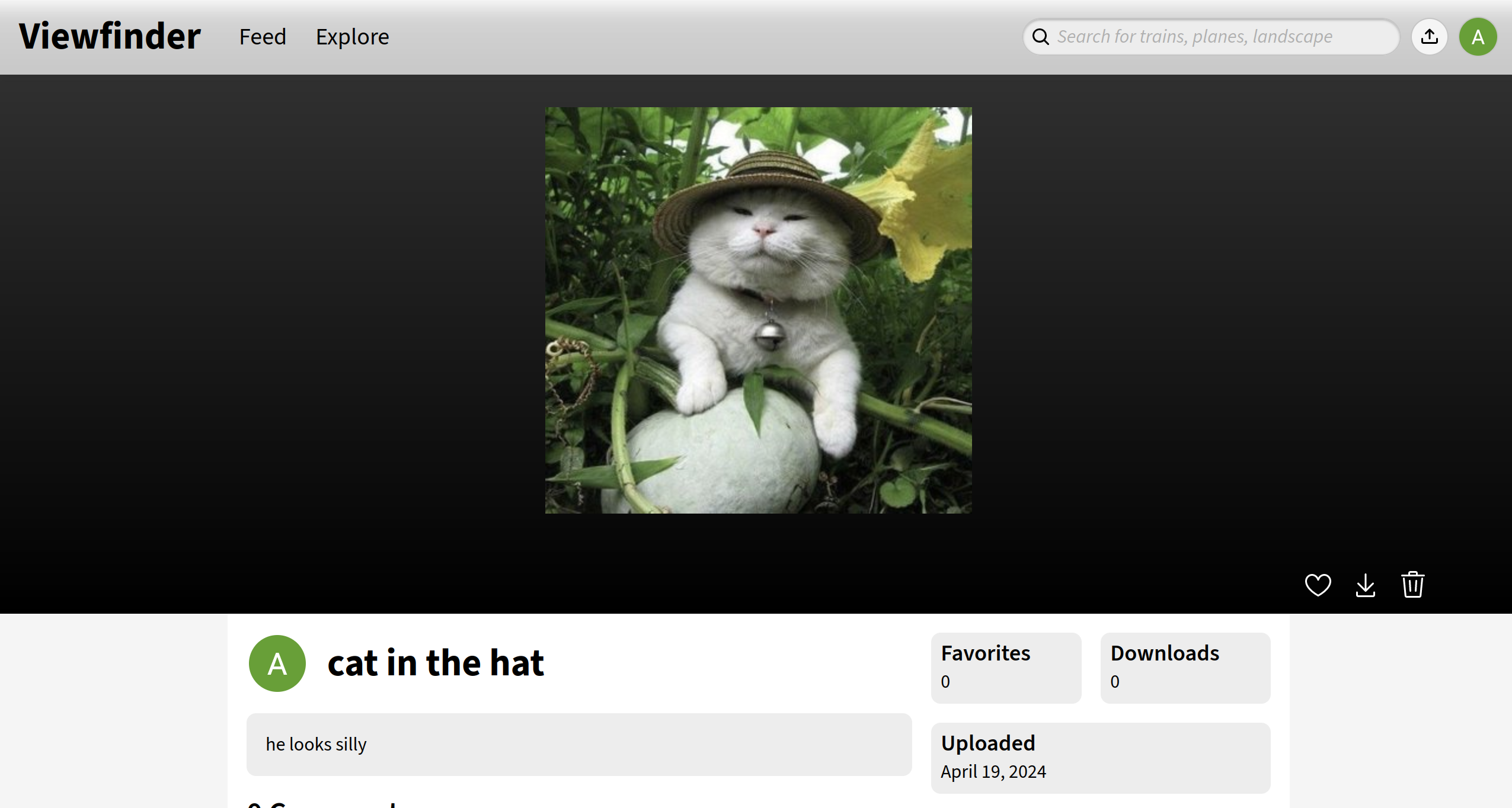

Once the image is created you can view the photo like you would expect:

Images are served from another endpoint which just retrieves objects from the MinIO cluster based on name. The MinIO client makes things super easy so this is dead simple.

// File: /src/routes/api/images/[uuid]

import { minioClient } from '$lib/server/minio';

import { S3_BUCKET_NAME } from '$env/static/private';

/** @type {import('./$types').RequestHandler} */

export async function GET({ params }) {

const image = await minioClient.getObject(S3_BUCKET_NAME, params.uuid);

return new Response(image);

};Deleting images

If the user wanted to delete the photo for whatever reason they have a button to do so. Clicking the delete button sends a DELETE request to our “photo editing” endpoint where the image is removed from our database, and then removed from MinIO.

// File: /src/routes/api/photo/[id]

import * as db from '$lib/server/mariadb';

import { lucia } from '$lib/server/auth';

import { minioClient } from '$lib/server/minio';

import { S3_BUCKET_NAME } from '$env/static/private';

/** @type {import('./$types').RequestHandler} */

export async function DELETE({ params, request, cookies }) {

// [...User auth stuff omitted]

if (!params.id) return new Response(JSON.stringify({ error: "Invalid request."}), { status: 400 });

let UUID = await db.getPhotoUUID(params.id);

if (!UUID) return new Response(JSON.stringify({ error: "Photo not found."}), { status: 404 });

return db.deletePhoto(user.id, params.id)

.then(res => {

console.log(res);

return minioClient.removeObject(S3_BUCKET_NAME, UUID)

.then(() => {

console.log("Object removed from min.io")

return new Response(JSON.stringify({ success: "Photo deleted."}), { status: 200 });

});

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

return new Response(JSON.stringify({ error: "Failed to delete photo."}), { status: 500 });

});

};This time we do a couple checks to see if the image even exists and if so, we delete the entry in our database and then from MinIO. Similar to the upload stage, we just string together a couple promises and things hopefully go as expected. I realize now that I deleted the database entry first which might leave the object still in MinIO if it fails for some reason. It may be better to reverse it so that if something fails users can still find the photo page and try to delete it again.

This is probably as simple as you can get, but it worked for our project. I’m sure you could do more fancy things, but since we were limited on time this is all we ended up doing. Thankfully, MinIO made it super easy, and given the opportunity I would absolutely use it again.